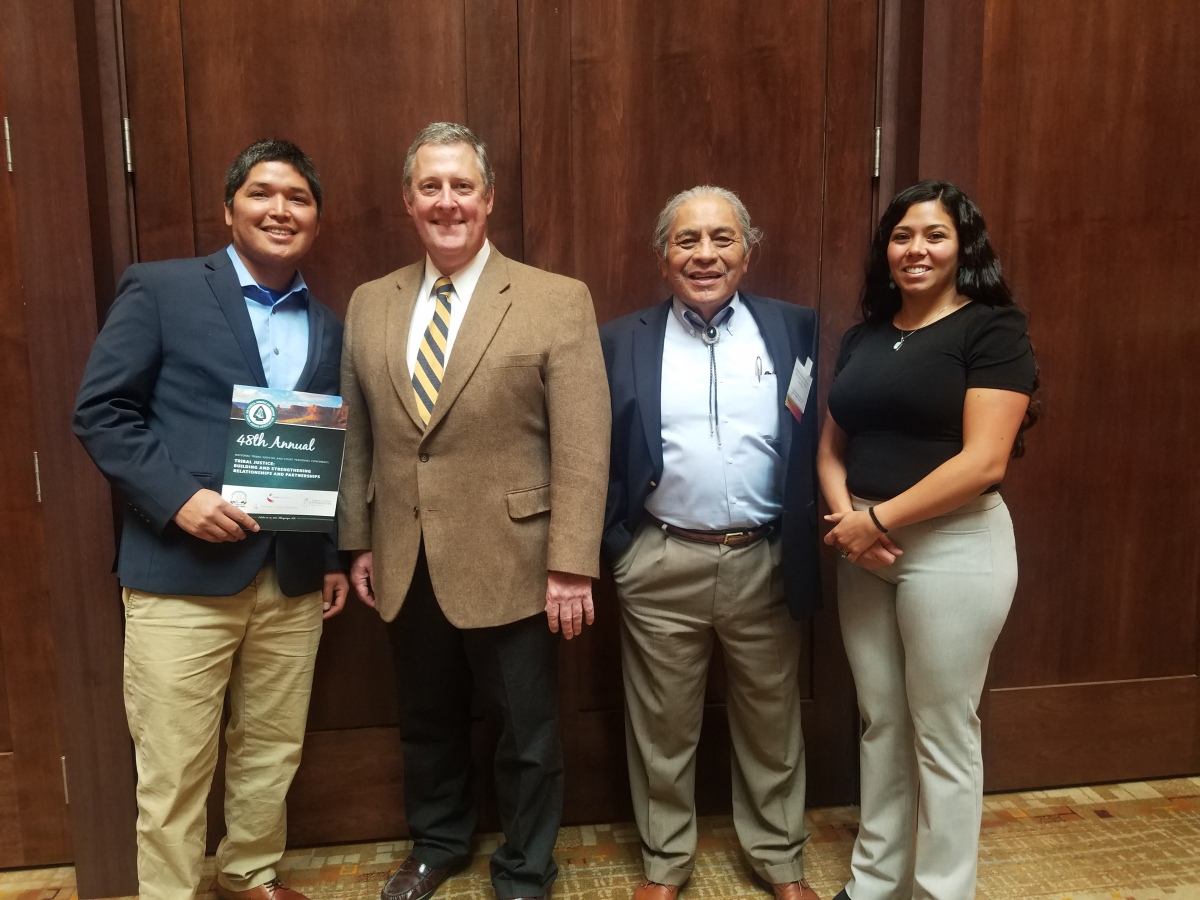

On October 10-13, 2017, the National American Indian Court Judges Association (NAICJA) held its 48th Annual National Tribal Judicial and Court Personnel Conference at the Isleta Resort and Casino. The theme of the conference was “Tribal Justice: Building and Strengthening Relationships and Partnerships.” NAICJA organized the conference for its members and networks of multiple Tribal court systems in order to strengthen and promote tribal sovereignty through education, information sharing, and advocacy.

One of many seminars at the conference was held by the Honorable Randolph Collins and the Honorable William Bluehouse Johnson, from the Acoma Pueblo Tribal Court, in a session named “How Tribal Self Determination May Save Civilization.” The session highlighted the issue of “State Recognition of tribal court orders.” Many tribes have issues with state courts not giving full faith and credit to Tribal Court orders like they do to other States. One solution Hon. Johnson highlighted was for states to amendment or enact statutes that would recognize and promote tribal justice resolutions for issues on the reservations. Statutes that recognize tribal court orders and foster reciprocity between the tribes and states would encourage better relations. Hon. Johnson highlighted North Dakota Rules of Court, Rule 7.2—Recognition of Tribal Court Orders and Judgments—as a model example:

“The judicial orders and judgments of tribal courts within the state of North Dakota, unless objected to, are recognized and have the same effect and are subject to the same procedures, defenses, and proceedings as judgments of any court of record in this state.”

Hon. Randolph Collins concluded the session by making an impressive philosophical connection between State-Tribal relations and Federal policies and laws. He noted that the states are laboratories of democracy and their relationships with Tribal Governments and Tribal traditions help shape federal policies and laws.

By Lyman Paul

Lyman Paul is a 2L students at UNM School of Law. He is from the Navajo Nation (Diné). He is of the Sleeping Rock People Clan (Tsenabił nii) and born for the Bitter Water Clan (Tódich’ii’nii). He is from Pine Hill, New Mexico on the Ramah Navajo Chapter, near Ramah, NM. He has a Bachelor of Science in Engineering in Civil Engineering from the Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, Arizona.